At the end of September 2024, western North Carolina and the surrounding states experienced 30 inches of rainfall over two days when an unnamed storm collided with Hurricane Helene over the mountains of Southern Appalachia. The resulting catastrophe laid waste to the entire region. At a time when misinformation, rising authoritarianism, and disasters exacerbated by industrially-produced climate change are creating a feedback loop of escalating crisis, it’s crucial to understand disaster response as an integral part of community defense and strategize about how this can play a part in movements for liberation. In the following reflection, a local anarchist involved in longstanding disaster response efforts in Appalachia recounts the lessons that they have learned over the past six weeks and offers advice about how to prepare for the disasters to come.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimated that Hurricane Helene poured 40 trillion gallons of water on the region. This caused an estimated 1800 landslides; it damaged over 160 municipal water and sewer systems, at least 6000 miles of roads, more than 1000 bridges and culverts, and an estimated 126,000 homes. There have been over 230 confirmed deaths across six states with many still missing.

The entire region was completely cut off from the outside world for a day or more, with all major roads shut down by landslides, collapsed bridges, and downed trees. Water, power, internet and cell service all went down within hours of the hurricane arriving, and remained down for days or, in some areas, weeks. There are still communities that will likely not have electricity for another three months because the roads that the power company would use no longer exist. Six weeks into this disaster, there are still tens of thousands of people who lack access to drinkable water. Not only have thousands of homes been wiped off the map—in many cases, the land they rested on no longer exists. Massive landslides have scoured canyons 30 feet deep, exposing bedrock that has not seen the light of day for tens of thousands of years. The torrential floods moved so much earth and caused so many rivers to change course that scientists have designated the hurricane a “geological event.”

In response, a beautiful web of mutual aid networks has emerged, saving countless lives by bringing in essential supplies, providing medical care, setting up neighborhood water distribution centers, solar charging stations, satellite internet hubs, free kitchens, free childcare, and more. Name a need and there are folks out here who have self-organized to meet it. We share these lessons we have learned in hopes of helping others to prepare for similar situations, aiming to increase our capacity to build autonomous infrastructure for the long haul.

Start Preparing Now

There is no time like the present to get organized.

Our mutual aid group has been around for almost eight years. Within 72 hours of the floodwaters receding, we had a functioning mutual aid hub and were mobilizing folks to check on missing people and chainsaw crews to cut people out of their homes and open up roads. We were only able to do these things because we had already put in the work in our community to build the trust and relationships that are so vital in times of crisis.

While we are a small group, we have an extensive network of friends and allies that has grown throughout years of smaller-scale mutual aid and organizing efforts. The best way to prepare for a disaster is not to stockpile supplies, but to build trust in your community and nurture a healthy web of relationships. The best way to accomplish this is to start doing mutual aid projects in your community before an acute crisis arises. This will give you practice operating as a group and organizing logistics, and it will also connect you with others you wouldn’t otherwise meet and show them that they can count on you. Because of the work we had already put in, when the crisis hit, people turned to us and spread the word that we are a good group to funnel supplies and money through. You can only build that kind of reputation by putting in the work now.

Communications

One of the biggest initial challenges we faced was that most means of communication went offline for between 24 hours and several weeks, depending on where you lived. That includes landlines, cell phones, and internet. We can’t stress enough the importance of having multiple back-up options in place to be ready for a situation like this. First of all, make sure you have a place and time established in advance where folks know they can find each other in the event of a disaster. This is probably a good idea even if communications don’t go offline—nothing beats face-to-face communication.

Satellite internet was invaluable during the first couple of weeks. For some particularly hard-hit communities, it remains the only means of communication six weeks into this disaster. Unfortunately, Starlink, which is owned by the white supremacist Elon Musk, has proven to be the most useful and the easiest to set up in a disaster scenario. We know from past experience that he is eager to suppress social movements that use his companies’ services. There are other companies that provide satellite internet, but it tends to be slower, with significant data limits. These are generally not mobile systems and would be challenging to set up in the middle of a disaster.

Don’t forget that you will need a source of electricity such as a generator or solar power to make satellite internet work.

Radios, especially ham radios, are another important means of communication that should be arranged in advance with people who already know how to use them. Our mountainous terrain limits the distance that radios can broadcast, but it would still have been helpful if we had possessed ham radios.

Supply Chain Logistics

Supply chain logistics are a huge piece of the puzzle. They will be one of your biggest headaches. In the first couple days of a disaster, you will probably only have access to the supplies you already have on hand in your immediate community. Stores will be closed and gas will not be available.

Soon, supplies will start pouring in from outside the disaster zone. The problem is that there will be a significant lag time between the announcement of a request for supplies and the time when those supplies arrive. In some cases, too many people will eventually answer the call, or by the time the supplies arrive, the needs on the ground will have changed. Social media can be useful in getting the word out about what supplies are needed, but it greatly exacerbates the lag time, especially as old posts are screenshotted and shared long beyond their relevance. When you make requests on social media, put a date in both the text and the visuals so people will know when the request was made.

Learn to anticipate what your needs will be a week from now, not tomorrow, because that is when the supplies will arrive. If and when regional support hubs are established, it is generally more efficient to communicate your needs directly to one of these hubs rather than blasting them on social media.

That being said, not every disaster is going to receive the kind of national spotlight that Hurricane Helene did. You may well find yourself in a situation where there are not enough donors or supplies.

Heavy Machinery

We need more people in our sphere that own or at least know how to operate heavy equipment. The floods destroyed hundreds of miles of roads and countless bridges. Massive piles of debris and tens of thousands of downed trees also blocked the roads, rendering many areas inaccessible. This is not the kind of problem you can solve with shovels and wheel barrows.

In many cases, communities that were totally cut off literally bulldozed their way to town; some used excavators to build new bridges out of pieces of the old bridges. It was not the state doing this work, but hillbillies who own heavy equipment who took matters into their own hands long before the state or federal government showed up. The rural activist scene is pretty well prepared to tackle anything involving a chainsaw, given that our network includes more than a few professional arborists and many of us already cut our own firewood. But we were not prepared for scenarios involving debris piles and earthmoving. Even beyond the immediate need of opening access to cut-off communities, heavy equipment such as dump trucks and track hoes remains crucial to the long-term demolition and clean-up work in the months following the storm.

Breaking the Spell

At the risk of repeating a cliché, acute crises such as natural disasters really do break the spell of normalcy that so many of us live under. Across western North Carolina, tens of thousands of people have experienced the joy of breaking out of the shell of isolated individualism and diving into the exhilaration and sense of purpose that collective action offers. Suddenly, people see that we are better off when we work in cooperation with each other, and that there are enough resources to meet everyone’s needs when we collaborate rather than compete. Even for radicals, there is a difference between knowing these truths intellectually and living, breathing, and feeling them 24/7.

To be clear, we don’t think that mutual aid groups should approach their work with the question “How do we radicalize people?” as the primary objective. Our primary goal should always be to save lives and make sure that people’s basic needs are met. But it is true that in the course of this crisis, thousands of people have gotten a taste of how we could organize society better. Many of them have a real hunger to keep that spirit alive but don’t know where to begin or where to plug in.

We should not show up in disasters the way that authoritarian or Christian groups do, looking to prey upon the vulnerable. Rather, we should make sure that there are ways that those who are radicalized by disasters and the experience of responding to them have opportunities to become involved in something lasting.

Rumors and Misinformation

Reliable information is hard to come by in a disaster. Even when phone and internet access return, rumors run rampant as everyone scrambles to figure out what happened and what kind of help is available or on its way. Many people will be deeply traumatized: when you have suddenly lost everything or your sense of stability has been pulled out from under you, fear and anxiety reign. On top of this, many of those joining in relief efforts will be running on pure adrenaline. None of these states of mind are conducive to clear thinking. It is important to get grounded and spread calm.

Do not repeat unverified information, especially on social media. If a statement starts with “my best friend’s uncle said…” or “I heard from a reliable source that…”, there is a pretty good chance that it is a rumor and not verified information. The more sensational the rumor, the more tempting it will be to spread it.

We can’t count the number of rumors that circulated here. Most of them only served to spread fear. “The military is coming in and shutting down mutual aid hubs and seizing supplies.” “Militias are out hunting FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] workers.” It is best to take note of such rumors and be prepared in the event that they turn out to be true, but in the meantime, to keep on doing what you are doing until you see otherwise with your own to two eyes. The best way to get reliable information is in face-to-face interactions with primary sources.

Ask questions of people as you are distributing aid. Whenever we did a supply run or a wellness check, we made sure to ask extensive questions, such as:

- “What are the needs here that aren’t being met?”

- “Has there been any help from the government yet?

- “Are there still missing people?”

- “What roads are open or closed?”

-

“Do you know of people who are still cut off from supplies?”

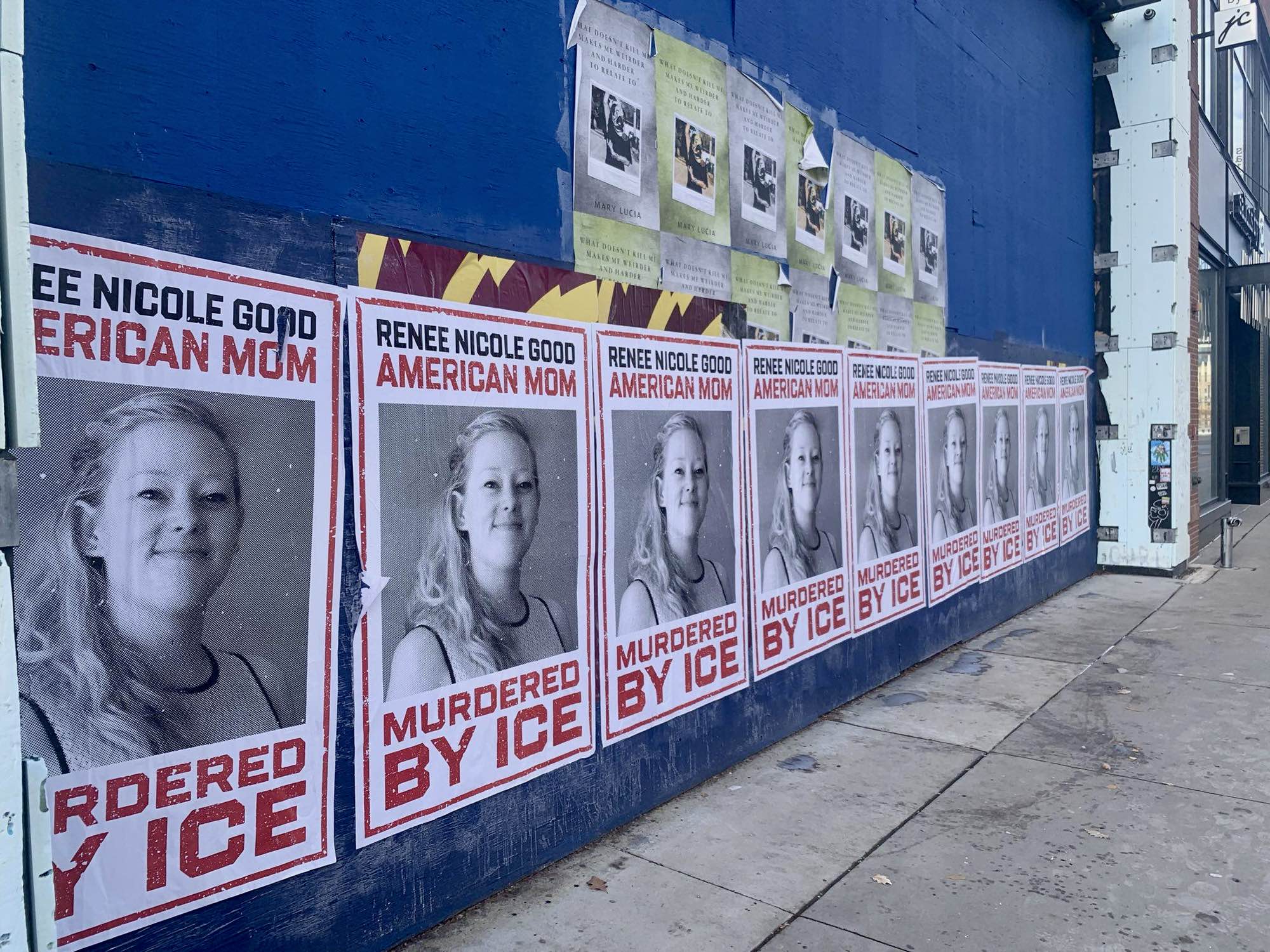

Vultures

Count on it: the far right will hurry to capitalize on any disaster, no matter what the scenario, in order to advance their fascist agenda. Within hours of communications returning, there were racist fake news stories alleging that Black and brown people were looting. Soon, these morphed into absurd claims that FEMA couldn’t help people because they had spent all their money on immigrants, and then into even wilder conspiracy theories suggesting that the government had manufactured the storm to disenfranchise Republican voters and that FEMA was going to seize people’s land for lithium mining. Never mind that there is no lithium to be found in the mountains of western North Carolina.

On top of this, many far-right and white nationalist groups made appearances in western North Carolina to provide aid. In most cases, they just showed up with a few supplies and left as soon as they had taken pictures to post on social media. It is worth distinguishing between groups that are part of the organized far right, like Patriot Front and the Proud Boys, who are only showing up to score political points, not to help people, and groups that really are there to provide direct aid but also happen to lean to the right. There should be no tolerance for the former. We feel that people should approach groups in the latter category with caution and evaluate whether it makes sense to work with them on a case-by-case basis. Crises make for strange bedfellows; there were a lot of Trump supporters working alongside anarchists to save lives, clear roads, and deliver supplies.

The best solution to countering the influence that the far right can build in disaster scenarios is to be better prepared and better organized. The groups that get the most done, deliver the most supplies, and do the most good are the ones that garner the most respect. It’s as simple as that. A good social media game doesn’t hurt, either. It is vital that we crank out reliable information and inspiring memes and narratives to counter the racist fearmongering that the far-right disinformation machine churns out.

Engaging with the State

We need more nuanced ways of thinking about government aid. Anarchists find themselves in a awkward situation in regards to FEMA and other forms of official government assistance. We rightfully criticize the government for its painfully slow and inadequate response to the disaster, but when the government finally shows up with significant resources, we aren’t sure how to engage.

We’d suggest that people should approach FEMA and similar organizations with the same cautious curiosity as aid groups that lean to the right but are not actively organizing for fascism. While grassroots mutual aid efforts are a thousand times more flexible and efficient in responding to disasters than the lumbering bureaucracy of the United States government, our access to resources pales in comparison to theirs when it comes to money, machinery, and labor. There is simply no way that we can crowdfund the estimated $17 billion in damages that Helene did. We need to strategically tap into those resources without compromising our principles or weakening our own efforts. Strategies such as helping people to navigate FEMA’s cumbersome aid applications and insurance claims can take pressure off our own fundraising efforts.

Another example of how we need a more nuanced approach to engaging with the government concerns the military. The presence of the military drastically changes the atmosphere in a community as soon as they show up. The communal feeling of mutual aid and cooperation can start to dissipate as their chain of command takes over. It is crucial to keep our mutual aid hubs completely separate from the military; do not let them staff or set up shop at our locations under any circumstances. But that does not mean we cannot strategically engage with them to use their free labor (and machinery) to muck out buildings, split firewood, and swing hammers.

The majority of military personnel are working-class folks in their late teens or early twenties who were sold a lie by military recruiters, a decision many of them come to regret. It will not hurt if they catch a glimpse of a better way of helping people.

Finances

Direct financial assistance is a huge need that most disaster relief groups are unable or unwilling to provide. If your group has the ability to raise large amounts of cash, you can be an absolutely invaluable resource in the days and weeks after the disaster. Donated supplies can only do so much.

In our case, tens of thousands of people have not only lost their homes, they’ve also lost weeks or months of employment. Bills are coming due and the overwhelming majority of folks are not getting anything close to the kind of assistance they need from FEMA or insurance companies. If you have a mutual aid group, set up a checking account in the group’s name and a few different digital wallets like Paypal and Venmo. Set up a website and social media accounts with clear links on how to donate. Do not wait for a disaster to do these things.

If you know that a disaster is on its way, take out a large amount of cash to have on hand. Remember, Venmo and credit cards are not going to work when the power grid and communications are down. We have found that most people are able to set up some sort of digital wallet if they need to, but it is important to have cash on hand for those who can’t.

It is also likely that if you are suddenly receiving and sending out large amounts of money in a short time, your account will get frozen or the people you send the money to won’t be able to access it immediately. This is infuriating, but there seems to be nothing that we can do about it—these companies have automated systems that flag accounts and they claim that they can’t override the system when your account is flagged.

Getting Organized

Grassroots disaster relief is no longer the exclusive province of church groups and small bands of autonomous mutual aid groups. The notion has gone mainstream since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when so many people discovered that their neighbors were all they had to count on. At this point, well-organized and well-resourced groups of every stripe are prepared to mobilize quickly—from reactionary right-leaning groups like the Cajun Navy and to networks of volunteer helicopter pilots, not to mention radical groups like Mutual Aid Disaster Relief. Beyond these specific groups, more people understand how to self-organize now. Within three to five days of the flood waters receding, you couldn’t drive more than ten minutes without running into a do-it-yourself relief hub or water station in someone’s front yard, church, or gas station parking lot. It would not be an overstatement to say that within a week, western North Carolina had the highest concentration of four-wheelers, all-terrain vehicles, and dirt bikes in the world, as people poured in from all over the South and beyond to help with search and rescue and to get supplies out to cut-off communities.

Most of these hubs were truly grassroots, with no formal organization behind them. This is an overwhelmingly positive development, but it does not come without challenges. The chief problems were redundancy of effort and lack of coordination between relief hubs, road clearing crews, and people doing supply runs, search and rescue, and wellness checks. The sooner you can develop relationships and good communication systems with other hubs, the better, so you won’t have to be constantly reinventing the wheel.

Creating an intake system for incoming volunteers and arranging for people to coordinate them is a huge piece of the puzzle. We had to turn away many offers of help in the first few weeks because we didn’t have a good system in place for fielding newcomers, especially those from out of town, nor could we guarantee that we could plug them into a project on any given day if they just showed up, despite the fact that there was always a mountain of work to do. Connecting volunteers to communities and individual homes that need medical care, mucking, gutting, and repairs requires an enormous amount of legwork on your part, not to mention building trust between you and the residents. You would do well to have someone in your group that has a deep love of spreadsheets.